Subjectivity, Objectivity and Frames of Reference in Evans's Theory of Thought

Adrian Cussins[1] This paper explores some problems with Gareth Evans's

theory of the fundamental and non-fundamental levels of thought

(Evans 1982). I suggest a way to reconceive the levels of thought

that overcomes these problems. But, first, why might anyone who

was not already struck by Evans's remarkable theory care about

these issues? What's at stake here?

[2] I shall say that experience and judgement are different

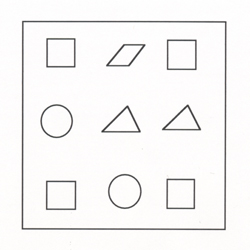

modes of cognition. I mean only that they are different

ways in which people have or exercise knowledge of the world.

There are diverse aspects to this difference; for example, the

kind of epistemic commitment involved in

experiencing the world differs from the kind of epistemic

commitment involved in forming judgements about the world. But

that will not be my topic here. There are also differences in

kinds of content: the characteristic content of

experience differs from the characteristic content of judgement,

which is truth-evaluable thought content. I will not here try to

defend a version of Evans's claim that the content of experience

is nonconceptual as contrasted with the conceptual content of

judgeable thought.1

Philosophers have often thought that the

content of experience is subjective, at least in

part, whereas the content of judgement is, or ought to be,

objective. Evans, for example, emphasizes the egocentricity of

how perceptual experience presents the world, and contrasts the

objectivity of his fundamental level of thought. And related to

this, it has often been held that judgements which are based

directly on experience -- for example, observational

judgements -- carry an essentially subjective element, whereas

judgements based on (fundamental) thoughts may be wholly

objective. It is this (supposed) third difference betweeen

experience and judgement that I want to pursue here, in

connection with the distinction between the non-fundamental and

the fundamental levels of thought, as applied to thoughts about

material, spatial objects.2

[3] As we will see, a central category, for Evans, of

non-fundamental concepts of spatial objects are those

which are based on experience, especially perceptual experience.

For example, demonstrative concepts of material objects in the

immediate environment of the thinker, which the thinker is now

perceiving, and where the demonstration of the object relies on

its being perceived.3 The way these concepts are of

their objects is fixed by the way their grounding perceptual

experiences are of their objects. Now if the

intentionality of these concepts is fixed by the intentionality

of the perceptual experiences on which they depend, and the

perceptual experiences are subjective, then it is at least going

to be a concern that thoughts based on these concepts will, in

part, be subjective. Hence the felt need for an independently

grounded level of thought which is not, in part, subjective. On

one reading, Evans's fundamental level is a level of

concepts of objects that are wholly objective; where being

"wholly" objective means being not at all subjective. It may be

that insofar as human minds realize a fundamental level of

thought, concepts that are "wholly" objective are rarely, if

ever, grasped; nevertheless, this sort of objectivity is the

ideal that governs the fundamental level of human

thought.4 We

need the fundamental level of thought to secure thought's

objectivity, as an ideal, and as best as is possible given human

limitations.

[4] So, on this reading -- a popular reading of Evans -- the

distinction in cognition between the subjective and the objective

maps on to the distinction between the non-fundamental and the

fundamental levels of thought: the subjective is non-fundamental

and the fundamental is objective. But, surely, what is not

fundamental is not necessary,5 so we can explore the idea of

cognition which exists entirely at the fundamental level. We can

conceive of, and explore in thought, what on this view would be

an idealization of human thought: a creature whose cognition was

exclusively "wholly" objective because all of the creature's

thought operated at the fundamental level of thought. I will call

such a creature a "Fregean Angel". Now this is what is at stake

here: Is human thought such that its idealisation would be the

thought of a Fregean Angel? We could pursue some philosophical

questions about the nature of human persons by engaging in a

quasi-theology: if the angels are modelled on the best in

humanity, then how should we conceive of the angels? Personally

I am not enamoured of Fregean Angels, but not because I don't

think we should strive for what is best in our cognitive natures.

I'd rather craft a different theological form, but what? And

what theory of cognition could legitimate such an alternative

form?

[5] I won't have very much to say about these last two

questions here, but I want to do some preparatory work by

exploring, in the context of Evans's account, what goes wrong

with the idea of the Fregean Angels. In seeing what goes wrong

with Angelic thought we can better see the nature of the error in

a theory of thought in which there is a "fundamental"

level at which objectivity is secured, which is autonomous of

subjective cognitive phenomena, and which is therefore

cognitively detachable from them. Maybe then we will be better

placed to offer one or two ideas about how to put this right;

about an alternative understanding of objectivity's role in

cognition. If, on the other hand, we find no incoherence in

Angelic thought then we may be unable to resist a conception of

human thought in which the subjective and the objective elements

are assigned to functionally, and philosophically, distinct parts

of the cognitive system.

[6] One way to understand what goes wrong with a metaphysical

picture of the world is to fill the picture out more, find

oneself getting into difficulties in filling out the picture, and

then to give a principled explanation for these difficulties.

Suppose we were to attempt this for a picture of objectivity

secured exclusively at the fundamental level, from which all

subjectivity has been detached. What could such thought and its

world be like?

[7] Think first about the basis for a distinction between

qualitative identity and numerical identity under such

conditions. Normally, if there are two objects which are

qualitatively identical to each other, we can understand that

they are not numerically identical (that they are two rather than

one) because we can imagine them given in different egocentric

presentations to the thinker, or with different significances for

action; for example, one on their left and one on their right.

But this idea is not available in our picture of a

"wholly" objective world, because all subjectivity is

eliminated from such a world, and the idea of being "to the

left" or "to the right" depends on a subject's egocentric

perspective on the world. Likewise significance-for-action

depends on different embodied, subjective ways of being in the

world. We need some other way of making sense of these

qualitatively identical objects being in different places.

Again, normally, we have no difficulty with the idea of

unperceived distinct places, but that is because we are already

conceptually equipped to operate with the distinction between

qualitative and numerical identity: we make sense of unperceived

different places because we can make sense of their being

distinct particular objects located at those places. But

we cannot appeal to that here because we are trying to make

metaphysical sense of this distinction that is presupposed in our

ordinary understanding of different places. What is entirely

legitimate in ordinary practice leads in this metaphysical task

to vicious circularity: numerical distinctness of objects is

explained by appeal to distinct places which in turn is made

sense of in terms of the idea of numerically distinct objects.

Both Strawson and Evans emphasize the explanatory

inter-dependence of objects and places, so in conceiving our

metaphysical picture we cannot rest numerical distinctness of

objects on distinctness of places, nor distinctness of places on

distinctness of objects. At the metaphysical level of

explanation these distinctions must be provided for

symmetrically. But how?

[8] It helps to start with a very simple world -- a world of

shapes -- and ask about the conditions under which one can make

sense of the idea of two distinct objects which are identically

shaped. Strawson (1959) is concerned with the possibility of

this distinction given that "we cannot at any moment observe

the whole of the spatial framework we use, that there is no part

of it that we can observe continuously, and that we ourselves do

not occupy a fixed position within it" (32). In contrasting a

situation in which the subject could monitor continuously the

spatial relations amongst objects he imagines the "world"

depicted in the figure below. I want to focus on a component of

this "world", its bound or frame of reference, which

provides an absolute spatial framework for the shape-world:

[9] If a world is presented at all to a Fregean Angel, it must

be presented in such a way that the entire extent of the world is

laid out before it, as the shape "world" is laid out for us

in the Strawson figure above. Subjects or thinkers cannot act in

this world; or, if they can, their thought about the world in no

way depends on their action in the world. The entire extent of

the world is laid out before the thinker, quite independently of

activity or experience, or embodiment: the world as a purely

formal object.

[10] In sum: if the fundamental level of thought is the level at

which objectivity is secured, and if the fundamental level can be

detached from any non-fundamental level, then we ought to be able

to make sense of an idealised cognitive creature that operates

exclusively at the fundamental level of thought and therefore

whose thought is "wholly" objective in that all subjectivity

has been excised from the thought of the creature. If thought of

any world at all entails the applicability of the distinction

between qualitative and numerical identity (for if it were not

applicable there could be no objects) then the world presented in

the thought of such an idealised cognitive creature would have to

be laid out before it so that the bounds of the whole world were

presented to it along with each object. The very possibility of

objects in such a world depends on their being co-presented with

the frame of the whole world. And the frame of reference itself

is not dependent on the objects in the world, or on action on the

world: rather, it is a transcendental condition on the

possibility of objects at all.

[11] This is not how it is with us! But it doesn't follow that

our cognitive theology is not like this. The question is this:

Does the explanation of why things are not like this with us

appeal to our imperfections; that, for example,

some of our singular thought is dependent on perceptual

experience, and our experience is egocentric and partial? For,

if so, the idealisation of human cognition -- which abstracts

from human imperfections -- would still be the cognition of the

Fregean Angel. And therefore the functionality of human

cognition would entail the coherence of the idea of a Fregean

Angel, which would stand as its model, just as soviet sculpture

in the former USSR modelled workers as their perfection: heroic,

unceasing and strong. Or as Evans's Generality Constraint (see

below) models the less-than-perfect compositionality of

humanly-grasped-concepts? On one view, what's going on with

Evans's fundamental level of thought is to secure a core part of

human cognition which -- unlike subjective experience -- would,

if perfected, sustain a metaphysics of the kind illustrated in

the Strawson figure. A question will be, what might drive Evans

to that, and is it possible to satisfy the motivation without the

Angelic theology? We will know that an alternative conception of

thought is needed because, as we will see, Angelic cognition

loses distinctions that play an essential role in the human

conception of objectivity, even as an ideal for human thought.

[12] Here is one reason one might think that that is what is

going on with Evans's fundamental level. Notice that the frame

of the world in an Angelic metaphysics need not be

geometric-spatial. It might instead be arithmetical: a

constitutive sequence, expressible for example with the integer

numerals, with respect to which the identity of numbers is given.

Identity and distinctness of numbers, like the identity and

distinctness of triangle shapes, makes sense only in relation to

such a canonical sequence. Evans brings out something just like

this when he introduces the notion of the fundamental level via

his discussion of abstract objects, and especially numbers. Since

it is the discussion of abstract, formal objects that

leads up to the fundamental level in Evans, we ought perhaps to

pay special attention to it.

7

[13] Suppose in playing a game one asked, "What number is

the square of a prime, the sum of two primes, and less than

twenty?" It would be a true answer, but a bizarre one, to

say "the number of planets". It would be bizarre

because the connection between the concept is the number of

planets and the concept is the square of a prime, the sum

of two primes, and less than twenty must be mediated

conceptually (one can't "see straight off" that

"the number of planets" is the answer). One could only

recognize "the number of planets" as a way of giving a

true answer to this question if one was in a position to judge

true the mediating thought, the number of planets is nine.

That is, the way of thinking of a number which is the number of

planets only connects to other ways of thinking of numbers via a

canonical way of thinking of numbers in terms of their location

in a canonical sequence, for example the sequence of integers.

Hence, the role of the concept nine in the mediating

thought. To give or understand "the number of planets"

as answer to the question is a two-step process: (1) the

number of planets is nine, and (2) nine is the square of a

prime, the sum of two primes, and less than twenty. Since a

thinker has to go via the mode of presentation of the number as

nine, one wonders why the answer is not expressed using

the same mode of presentation; hence the appearance of

bizarreness.

[14] In order to understand what it is for numerical properties

to apply to a number, one must be able to think of the number in

terms of its location in a canonical sequence, so we could call

this way of thinking of numbers in terms of their location in a

canonical sequence, the "fundamental" way. Other ways

of thinking of numbers -- for example, as "the number of

planets" -- are non-fundamental, because it is only possible

to understand how concepts of numerical properties can be

predicated of them if the thinker knows what it would be

to identify a number so thought of with a number thought of in a

fundamental way. (This restriction doesn't, of course, itself

apply iteratively to fundamental ways of thinking of

numbers).

[15] One could go on from here to the following idea: if the

thinker were attempting to think about a number in a

non-fundamental way, then we should say that the thinker wouldn't

know what they were thinking about if they didn't know which

number they were thinking about, and they wouldn't know which

number they were thinking about if they weren't in a position to

understand the truth conditions of a range of arithmetical

predications of the number. But since arithmetical predications

to numbers make sense only via a fundamental way of thinking of

numbers, a thinker wouldn't know what they were thinking about if

they didn't know what it would be for a thought of the form

<this number is d> to be true

where d is a fundamental way of

thinking of the number. Satisfaction of "Russell's

Principle"8

requires a fundamental level of ways of thinking

of numbers, and it requires the explanatory dependence of

non-fundamental ways of thinking upon fundamental ways of

thinking. Hence the necessity of the two stage procedure noted

above, which is emphasized wherever Evans talks about the

fundamental level of thought.

[16] Notice the equivalent role played by the canonical integer

sequence in thought about numbers and the absolute spatial frame

of reference in thought about shape-objects in the

Strawson-world. Both are absolute frameworks in that the

identity and distinctness of their objects is explained in terms

of the frame of reference, but the frame of reference itself is

not explained in terms of the objects. Both frames extend to the

limits of their world (there cannot be more objects than can be

discriminated with respect to their frame). And in both cases

objects must be co-presented in thought with their frame of

reference: even if one thinks of the objects in a non-fundamental

way, one's understanding of which object is in question (its

satisfaction of Russell's Principle) rests on understanding of an

identity claim in which the object thought of non-fundamentally

(the number of planets, the shape I am thinking of)

is identified with an object thought of in terms of its location

relative to the absolute frame of reference (the number

nine, the triangle at the top left of the frame).

That is, the frame must itself be represented in thought,

in the same kind of way as non-fundamental concepts

are explicitly cognitively represented: understanding which

object is in question rests on understanding the identity

proposition, and in the identity proposition the framework

concept d stands symmetrically

across from the non-fundamental concept. Russell's Principle is

satisfied only because the frame of reference is rendered

explicit at the fundamental level of thought. The frame itself

figures as a conceptual constituent in thoughts which must be

understood if even non-fundamental thought about particulars is

to be possible.

[17] Impressed by this account of thought about numbers, Evans

-- on this reading -- develops an analogous account for thought

about material, spatial objects. The analog of the canonical

sequence which is constitutive of numerical identity and

difference is an objective frame of reference for spatial

objects. It is not possible that the frame of reference for

human thought extends to the limits of its world, but the frame

plays the equivalent role for human thought that the absolute

frame plays in the number and shape examples: it acts to secure

objectivity, in the sense of securing uniqueness and distinctness

for objects without relying on experiential or other

non-fundamental ways of thinking. In the material, spatial-world

the frame provides for the possibility of thought which is

from no point of view, which -- by contrast with

egocentric thought -- is necessary for objectivity. Moreover,

Evans claims that satisfaction of Russell's Principle for thought

about material, spatial objects rests on being able to bring into

"alignment" one's egocentric presentations with a conception

of the spatial world which is from no point of view. And, as we

will see, Evans claims that satisfaction of the Generality

Constraint for thought about material, spatial objects requires a

fundamental level of thought at which a thinker can make sense of

a full range of predications.

[18] So in this domain too, thought about objects involving

non-fundamental concepts requires a two-stage procedure: to

understand the thought that <a is F> where a

is a non-fundamental concept of an object grounded in egocentric

experience, the thinker must know (1) what it would be for

<a = d> to be true, for a

fundamental way of thinking of an object, d, which is from no point of view

because it exploits an objective frame of reference, and (2) what

it would be for <d is

F> to be true. Thus the frame of reference must be

cognitively represented, so that it is itself presented in

thought ("d")

whenever one thinks of a spatial object. Experience-based thought

about spatial objects is explanatorily dependent on thought about

objects at the fundamental level of thought, which is

"wholly" objective, because "from no point of

view", because anchored by an absolute (if still partial)

frame of reference. And fundamental thought of objects is not

explanatorily dependent on experience-based thought; it can

detach itself from experience-based thought. The objective frame

of reference, on this view, is not a special way of employing

egocentric presentations, or presentations of the world as

activity, because it is constituted by a fundamental kind of

concept, the ds, which present

objects from no point of view, and therefore not experientially

and not in terms of embodied activity. In this sense, then, the

fundamental level of thought about material, spatial objects,

like fundamental thought about numbers and about the Strawsonian

shape-world, is a formal level of thought.

[19] We need now to explore a little how frames of reference

work, so as to be able to distinguish between "pathological"

and "healthy" uses of frames of reference in cognition. I'm

going to suggest that frames of reference, if they are to

successfully provide for the possibility of singular reference

must (1) not be explanatorily independent of the identity of

particular objects that are located with respect to the frame,

and (2), must not figure explicitly in thought, by being directly

cognitively represented at a special level of thought. For, if

they are so represented and they do so figure, they will prevent

the possibility of successful singular reference. Thus we should

abandon the model of the fundamental level of thought about

material, spatial objects that we arrived at via the Angelic

metaphysics of the Strawson shape-world, and Evans's discussion

of thought about numbers; the model in which the frame must be

independent of and co-presented with the objects. We will need

some other way to secure the "objectivity constraints" of

Russell's Principle and the Generality Constraint. The payoff, I

hope, is to gain a richer sense of the contrast between a

formalist conception of thought and of metaphysics, and a

non-formalist conception in which experience provides for the

possibility of objectivity. This opens up a quite different

conception of experience than that which is

subjective-in-the-sense-of-anti-objective.

[20] Let's begin this discussion by distinguishing thought which

is relative to a frame of reference from thought which is

dependent on a frame of reference. First a couple of

examples of frame-dependence.

[21] A subject might make a reference to a chess piece which is

relative to the frame of reference established by the chess

board. I am thinking here of a game of chess not as a

spatiotemporally located episode, but as a formal type whose

existence is independent of any particular spatio-temporal

context, constituted solely as a sequence of moves which might be

materially manifested in any number of different places and

times. For example, the subject might say "black's bishop

moves to Queen-Bishop-4" referring to a move in a game

between Kasparov and Deep Blue. The reference to the chess piece

is relative to the frame of reference which is established by the

chess board; not by any particular chess board situated in the

space through which the thinking subject moves, but relative to a

general or abstract frame which does not belong to the unified

spatio-temporal framework in which actions and material objects

are situated. Such a reference is not only relative to a

frame of reference but is frame-dependent because the

chess-piece in question cannot be identified independently of the

frame of reference established by the generic chess board. The

idea of that particular makes no sense at all

independently of the frame of reference of the chess-board. In

such cases the ability to think about the chess piece is

dependent -- both explanatorily and ontologically -- on the

ability to think about the frame of reference of the chess board,

but the ability to think about this frame of reference is not

dependent on the ability to think about that chess piece. This

sort of asymmetric dependence is characteristic of

frame-dependent reference.

[22] Consider my ability to think about Piggy which is relative

to the reference-frame established by William Golding's book

The Lord of the Flies. I can talk quite happily about

Piggy, even counterfactually about what Piggy would do in various

imagined circumstances, but only so long as I stay within the

reference-frame established by the story.9 If, walking down the

street, someone asks me, "Is that Piggy?", the question

makes no sense unless it is reinterpreted to mean something like

"Doesn't that person look just like what you imagine Piggy to

look like?", or perhaps, "Isn't that the person who was a model

for Golding's depiction of Piggy?", or something of the kind. I

can identify the person walking down the street without

necessarily having to identify anything else, but an actual

identification of Piggy would require the identification of the

objects and places that constitute the story-frame with respect

to which references to Piggy are made. But the story-frame

exists only in Golding's world, not in Piggy's. The cognitive

resources for epistemic access to Piggy are exhausted by the

frame of reference provided by the story. Therefore,

Piggy-references cannot escape the story-frame of The Lord of

the Flies; references to Piggy make sense only internally to

the frame. References to Piggy are not only frame-relative.

They are also frame-dependent. Again we have the characteristic

asymmetry of frame-dependence: Piggy-references are situated and

made possible by the story-frame, but William Golding's

story-frame cannot itself be situated within a space in which

Piggy acts.

[23] One might say about thoughts of Piggy and the chess piece

that they are descriptive thoughts; that they identify their

objects purely descriptively. But it is important to see that

not all descriptive identification is frame-dependent. What is

important to the argument is not so much the distinction between

descriptive and singular content as it is the distinction between

frame dependent identifications and frame relative

identifications of objects. Thoughts based on certain kinds of

definite description or universal quantification are

frame-relative. If I think about the tallest Cornell Professor,

qua tallest Cornell Professor, (and I have no other way

available to me of thinking of this person) then I think about

some particular person only relative to a reference-frame which

establishes a set or a totality: the population of Cornell

Professors, with respect to which the expression "the tallest

Professor" may fix a unique object. In cases like this, a frame

of reference is established not by a fictional story, but in

order to interpret the semantics of a definite description, or of

a quantifier ("all Professors", "most Professors"). My

understanding of which particular Cornell Professors there are

rests, in part, on my grasp of the totality of Cornell

Professors, but it is also true that my understanding of the

totality which is the population of Professors can (at least in

principle) rest on my understanding of what it is to be each of

the members of this totality. Hence my reference to the tallest

Professor is not frame-dependent: the characteristic asymmetry of

frame-dependence does not obtain in these cases. In this example

we use a frame-relative semantics to interpret the definite

description, relying on our background understanding of

particular individuals (particular Professors) to ensure that the

meaning of the description is not frame-dependent.

[24] In certain other cases escape from a frame-dependent

semantics may not be so smooth. Consider thinking about a person

as the tallest spy. If I am given a totality -- the population

of spies -- then I am in a position to think about a particular

as the tallest spy. But how might I be given the totality? I do

not have some prior general understanding of spyhood which

determines its own application to particular objects

independently of knowledge of those particulars. My

understanding of the predication of spyhood to Jones draws

equally on my inter-dependent understandings of spyhood and of

the special character, history and circumstances of Jones. My

understanding of spyhood is dependent on my understanding of what

it is for Jones to be a spy, and what it is for Smith to be a

spy, and so on for a small number of particular spies of whom I

have knowledge. I may have an understanding of these very

particular cases of spy-hood but not in a way which generalizes

to allow me an understanding of what it is for an arbitrary

particular to be a spy. So I cannot generate an intelligible

idea of the totality of spies either through a general concept of

the universal spyhood which independently determines its

own application to particular objects, or through an inductive

understanding -- for the cases of Smith and Jones and so forth --

of what it is to be a particular spy. The semantics, however,

still requires the totality of spies. Since the totality

cannot be given in terms of what is available to be understood in

the predicate "spy" or in particular instances of spyhood,

it must be supposed to exist independently of what can be given.

If the thought of the tallest spy is not to be an illusion, the

world -- but not the world as experienced, or acted on or

otherwise made intelligible -- must somehow provide a

"frame" which bounds the spies from the non-spies. Such a

"noumenal" frame would delimit the totality of spies, it

would outrun my (and anyone else's) understanding of the

predicate "spy", and it would be independent of the

particular known cases of spyhood that fall within it. Thus the

attempted thought about an object as the tallest spy would be

frame-dependent; it would exhibit the characteristic

asymmetric dependence of individual object on totality or frame.

A putative thought about a particular by means of the descriptive

content the tallest spy would, in that case, fail in a way

which is analogous to the failure of a thought about the actual

Piggy: the frame required for the intelligibility of the totality

of spies is a fictional projection onto the world. Or, it might

be preferable to put the point a little differently (picking up,

for example, on a disanalogy due to the intentional

fictionality of Piggy) like this: there could be nothing in our

understanding which would provide for the intelligibility of a

distinction between the frame of reference being fictional and

its being actual; hence the idea of its presupposing a

"noumenal" world. But either way, both "Piggy" and

"the tallest spy" are frame-dependent, and either way the

frame-dependence disables an understanding of these terms as

referring robustly to an objective reality. That this is so does

not entail a complete breakdown in meaning; that's part of

what makes these cases interesting.

[25] This discussion suggests a hypothesis: that where

non-abstract objects are in question, successful and intelligible

reference to a particular requires that, if the reference is

frame-relative, it not be frame-dependent. Moreover, the

distinction between reference to actual material particulars on

the one hand, and reference to fictional objects, or virtual

objects, or representational objects (the woman in the painting)

or merely ideological objects ("most spies", "most

liberals", "most terrorists", "most freedom fighters"),

or objects which are defined by the rules of a closed formal

system, on the other, is to be understood in terms of the

distinction between reference which is merely frame-relative and

reference which is frame-dependent. The hypothesis is that it is

constitutive of any intelligible notion of being actual -- and of

not being fictional, virtual, representational, ideological or

formal -- that reference to the object not be

frame-dependent.

[26] If this hypothesis is correct then the account, considered

above, of the fundamental level of thought about material,

spatial particulars -- which was suggested by the model of

thought about numbers and motivated by a certain conception of

objectivity -- cannot be right. In order to establish a level of

thought uncontaminated by egocentricity or subjectivity, appeal

was made to an absolute spatial framework with respect to which

spatial objects stood in a relation of asymmetric

dependence. But, as we have seen, this kind of asymmetry is

characteristic of frame-dependence. Therefore, on that reading of

Evans, his fundamental level of thought would be frame-dependent,

and so unable to sustain distinctions between reference to actual

objects and reference to fictional or merely representative

objects. But the applicability of such a distinction is a

necessary component in objectivity. Hence, that conception of

thought would fail to satisfy its governing motivation.

[27] It does not help to respond that Evans does not suppose

that his fundamental level can, in humans, eliminate subjectivity

altogether. For the model of the fundamental level would

still be in intact. On that conception of thought, subjectivity

is only an imperfection, and so would entail the coherence of the

Angelic metaphysics. And if the argument just given is correct,

the Angelic metaphysics cannot sustain the distinction between

the fictional and the actual. If reference to any

material thing in the world were relative to the Angelic frame of

reference which limns the extent of the world, then there would

be no content to the distinction between the world's being actual

and the world's being fictional. (The problem with being an

angel is that there would be no gap between dreams and

reality).

[28] I will come later to the second objection to an objectivist

theory of thought, but I want now to consider (a few ideas about)

how an alternative conception of thought might work; a conception

which does not abandon objectivity but reconceives it, not in

oppositional contrast to subjectivity, but rather in contrast to

being a mere information-processor. Thought, even at its most

sophisticated and most fundamental, essentially entwines elements

of subjectivity with elements of objectivity. Put more strongly

the conclusion would be that the objectivity of thought entails

the subjectivity of thought.

[29] We can begin this part of the discussion with what Evans

would classify as non-fundamental concepts of material, spatial

objects. They are non-fundamental at least because they

essentially rely on experience, and embodied activity, and

therefore necessarily incorporate subjective elements. With our

eye towards a more positive account, we are to consider whether

these kinds of concepts could satisfy Evans's guiding motivation

to secure the objectivity of thought. And therefore whether

objectivity can be secured without introducing a special level of

thought -- the fundamental level -- which is independent of

experience and subjectivity.

[30] Suppose I think of a house as number 12, 32nd Street,

downtown then my identification of the house is relative to

the street grid and numbering system for downtown. My ability to

think of the house is not, however, wholly dependent on

the frame of reference provided by the street grid, because I can

gain information from the house, or information which is

house-directed, which is not relative to the street grid, and I

am able to coordinate my judgements and my actions with respect

to these different sources of information. For example, I have

available to me not only descriptions which are given relative to

a street grid, but also a map of downtown which locates the house

relative to other objects based on distances and directions (and

not the street grid) which are given relative to the map-based

frame of reference. I may also have directions for driving to

the house given to me verbally by a trusted and reliable friend

which consist of a sequence of instructions to turn left or to

turn right or to go straight ahead. When I get near to the house

I can ask passers-by if they know where number 12, 32nd street

is. I may have information through memory about the appearance

of the house. What is important for my understanding of which

house is in question is that, whether or not I decide to visit

the house or to form judgements about the house, I have an

epistemic capacity to coordinate information so as to guide my

actions and judgements in a way which is appropriate or sensitive

to that particular house. It may be that there is some

misinformation in what is available to me, and that my

capacity to coordinate amongst the information sources

compensates for these errors, keeping my identification of the

house robustly on target. An important part of the robustness of

my identification of the house may consist in my ability to

recover from guidance errors due to misinformation amongst my

sources. This kind of coordination and recalibration of multiple

frames of reference -- even though each individual frame may be

subjective -- is what eliminates the threat of frame-dependence

from my knowledge of which house is in question. I exploit many

frames in conceptualising the house, but my cognitive resources

for epistemic access to the house are not exhausted by these

frames of reference.

[31] References to particulars are often not frame-dependent

because they have this kind of structure: they are based on the

coordinations of many different frames of reference, which

are illustrated in the house example. I do not mean that they

are dependent on some number of frames of reference greater than

one; that would result in frame-dependence just as much as the

chess example. What I mean is this: a subject's understanding of

which particular is in question does not consist primarily in

knowing the position of the object relative to one or more frames

of reference, but rather in the subject's knowledge of how to

coordinate different frames of reference so as to be able

to judge appropriately or to act appropriately with respect to

the particular object. What I want to suggest is that if there

is a fundamental level of cognition, it is not a special level of

thought, or a uniquely privileged frame of reference, but

rather a capacity to coordinate amongst frames of

reference, and, when necessary, to generate and establish new

frames of reference. We can, in fact, read in this way what

Evans has to say about cognitive maps which ground his

fundamental level. At the level of thought and reference there

would be frames of reference, all of which would include

indexical, demonstrative and first-personal components.

Objectivity, however, would not be secured at this level, but at

a nonconceptual level of capacities and map-like representational

devices whose function is to provide for holistic coordinations

amongst diverse frames of reference.

[32] Coordination of frames of reference often involves

sufficient redundancy to allow for the management of error (as

well as the management of subjectivity). Because the subject's

understanding of which object is in question consists in the

subject's knowledge of how to coordinate amongst multiple frames

of reference, the subject's frame-internal knowledge is not

autonomous. In such examples, a subject's ability to think about

the object in question may depend on the subject's ability to

think about a frame or frames, but it is also the case that the

subject's ability to think about the frames rests on the ability

to think about particulars which are structured by the frame. It

is because of this that errors in a frame of reference may not be

damaging to either action or judgement, that the management of

error can be robust, and that we can make sense of a whole frame

of reference being in error. The subject's ability to think

about the house depends initially on his ability to think about

the street grid, but, as the coordinations develop, his

understanding of the frame of the street grid is also based on

his capacity to think of the house, and other places, as given

within a map of the area, or as reachable by a sequence of turns,

or as having certain characteristic appearances from privileged

vantage points. Successful frame-relative thought of a

particular does not exhibit the asymmetric dependence of the

chess, Piggy and "the tallest spy" examples, and this

affects directly the kind of normativity (error, correctness,

guidance, etc.) that governs adequate singular reference.

[33] We can see both similarities and differences between these

ideas about objectivity's resting on coordinations amongst

multiple frames, none of which are privileged, and an alternative

reading of Evans that moves away from the account of the

fundamental / non-fundamental distinction as the distinction

between subjective and objective levels of thought. The

alternative reading understands the fundamental / non-fundamental

distinction as the contrast between thought which is relative to

an egocentric frame of reference and thought which is relative to

a holistic frame of reference. On this new view of Evans, a

non-fundamental concept identifies its object relative to an

egocentric frame of reference. A fundamental concept identifies

its object relative to a frame of reference which is both

non-local and holistic: it is non-local in that the body of the

subject does not have a privileged role for identifications

relative to the frame, and it is holistic in that the

identification of each place is supported by the potential

identification of any or all of the other places. So, when Evans

requires for non-fundamental thought not only knowledge of

location in egocentric space but also knowledge of what it would

be for something identified egocentrically to be identical to

something given at the fundamental level of thought, he is

requiring that the subject be able to coordinate the two frames

of reference: there must be cognitive resources for identifying a

position in the egocentric frame of reference with a unique

position in the non-local, holistic -- and, in that sense,

objective -- frame of reference.

10

[34] What Evans has to say about cognitive maps fits much better with this alternative interpretation than with the objectivist interpretation. It is true that Evans says (on page 152) that fundamental thought which is grounded in a cognitive map "is truly objective -- it is from no point of view", but Evans also explicitly denies that "from no point of view" means from a God's-eye point of view, or even from a third-person point of view. It may well be that Evans's notion of objectivity here -- unlike the notion which is contrasted with subjectivity -- is quite compatible with identifications of objects and places which depend on the subject's current spatio-temporal location, and which are therefore indexical, or first-personal, or demonstrative. But if the cognitive map sustains indexical identifications, what becomes of the distinction between the fundamental and the non-fundamental levels of thought? What matters for Evans about the fundamental level is not non-indexicality or anti-subjectivity or avoiding the contingencies of a subject's idiosyncratic location, but rather securing objectivity via the holistic coordinations amongst objects and places. Consider, for example, how cognitive maps are introduced on page 151:

The places which we think about are differentiated by their spatial relations to the objects which constitute our frame of reference.... Hence a fundamental identification of a place would identify it by simultaneous reference to its relations to each of the objects constituting the frame of reference. A place would be thought about in this way if was identified on a map which represented, simultaneously, the spatial relations of the objects constituting the frame of reference. This identification has a holistic character: a place is not identified by reference to just one or two objects, and so the identification can be effective even if a few objects move or are destroyed. Our identifications of places has this holistic character whenever we rely in our thinking about places upon what has come to be called a "cognitive map": a representation in which the spatial relations of several distinct things are simultaneously represented.Notice that there is no reference in this passage to non-indexicality or non-egocentricity. It is holism which is emphasized. It is true that several paragraphs later, Evans does say that "each place is represented in the same way as every other; we are not forced in expressing such thinking, to introduce any 'here' or 'there'". The alternative interpretation notes that each side of the semi-colon expresses the same claim, and that therefore we should interpret "not being forced to introduce [indexicals or demonstratives]" as being equivalent to "representing each place [and object] in the same way as every other". What I think Evans wants is (1) to think of a cognitive map as constituted by its uses, rather than by intrinsic properties; (2) that the uses of a map will often involve indexical and demonstrative modes of presentation, but that (3) this is still compatible with the cognitive map's securing the objectivity of the fundamental level. The "heres", "theres", "thises" and "thats" disperse across the map in different uses of it; the map itself does not fix, at a time, some place as "here" or some object as "that one"; the "you are here" pointer is not part of the cognitive map, but has a varying location in the map depending on the changing alignment of the egocentric frame of reference with the cognitive map. The map does not force us to use "here" of a particular place or "that" of a particular object, for that would be a map which allowed thought from only one particular point of view. That is how an egocentric frame works, but not a frame which is "from no point of view".

[35] This kind of interpretation is most strongly supported in a passage in chapter 7 (211-212):

Why should we suppose that everything that is true can be represented [in non-indexical] terms?... Just as our thoughts about ourselves require the intelligibility of the link with the world thought of "objectively", so our "objective" thought about the world also requires the intelligibility of this link. For no one can be credited with an "objective" model of the world if he does not grasp that he is modelling the world he is in -- that he has a location somewhere in the model, as do the things that he can see. Nothing can be a cognitive map unless it can be used as a map -- unless the world as perceived, and the world as mapped, can be identified. For this reason, I think that the gulf between the "subjective" and "objective" modes of thought which Nagel tries to set up is spurious. Each is indispensably bound up with the other.This passage denies directly the thesis of detachability required for the idea of a creature whose cognition was "wholly" objective. The passage is ignored or set aside in objectivist interpretations of the fundamental level because it runs counter to so much else in the book (given that the book was unfinished at Evans's death, it is not surprising that there are some tensions between, for example, chapter 6 and chapter 7). Thus in section 3 of the appendix to chapter 7 -- though in the context of offering an alternative formulation of the fundamental level -- we find, "one must conceive the states of affairs one represents in one's 'egocentric' thoughts -- thoughts expressible with 'this', 'here' or 'I' -- as states of affairs which could be described impersonally", which suggests, given the <a = d> form of Evans's account, that the constituent concepts of the cognitive map are impersonal, non-indexical, and non-demonstrative, or would be so treated by the version of the theory being considered in the appendix.

[36] It is at this point in the appendix -- where alternative accounts of a subject's satisfaction of Russell's Principle are in play -- that the threat of frame-dependence arises for Evans's fundamental level.11 The matter is left unresolved, finishing with the plaintive "It still seems there is something right about §6.3...". What I think Evans came to see was this: Holism of the cognitive map is sufficient for it to represent each object and place in the map in the same way as the other objects and places that figure in the map. Holism is thus sufficient for not being forced to introduce a "here" etc. for some particular place. But, nevertheless, holism is not sufficient for objectivity because -- given that the extent of the map's representation is very partial, unlike the "formal" cases we considered -- the identification of the frame objects and places would still be egocentric. (There may be no determinate fact as to which objects and places are the frame objects and places; in which case the egocentricity will distribute holistically across all the objects and places. It would thus remain true that "each object and place is represented in the same way as every other" but that they are all somewhat "contaminated by egocentricity").

One must conceive the states of affairs one represents in one's "egocentric" thoughts -- thoughts expressible with "this", "here", or "I" -- as states of affairs which could be described impersonally, from no particular standpoint.If the problem is just left like this, it is devastating for Evans's account, whose point all along had been to show how to satisfy a strong reading of Russell's Principle compatibly with realist truth conditions; to show that "the requirement of discriminating knowledge [for thought] is to be justified outside a verificationist framework" (106). It is because of the problem of the appendix, rather than any other difficulty in the book, that it's being an unfinished posthumous work has prevented the project from being completed.

But there is a problem about what exactly this requirement comes to -- what exactly it is to know what it is for an arbitrary element of the objective order to be this, or here, or me.... But it is not clear what we should make of the requirement if we do not suppose that the subject can formulate, and in favourable circumstances decide the truth of, propositions of these kinds [<a = d> and <d is F>]. And it seems that we are not entitled to that supposition. Section 6.3, for instance, gives the impression that the objective or impersonal mode of thought about space can be understood as a mode of spatial thinking organized around a framework of known objects and places -- the "frame of reference". But such a mode of thinking will not be capable of achieving a higher degree of impersonality that that achieved by the subject's thought about the objects and places which constitute the frame; and (especially if we think here about Twin Earth cases), it seems plausible that a subject's right to be counted as thinking about these familiar objects and places turns partly on his conception of the role they have played in his past life -- being visited by him, seen by him, etc.... In that case, the seemingly objective mode of thinking about space is, after all, contaminated by egocentricity. (1982: 264 - 265)

[37] To escape the problem entails abandoning the form of

Evans's theory in that it entails abandoning both the fundamental

level of thought at which objectivity is secured, and the

two-stage procedure for understanding (<a = d> and <d

is F>) which was introduced, and made most sense, in

connection with thought about abstract objects. But the

motivations that were important to Evans are still intact, if we

shift the objectivity-securing work of holistic coordinations to

a nonconceptual level -- not itself a level of thought and

concepts -- at which frames of reference are established, aligned

and re-aligned with each other. We can, then, allow that

every frame of reference will include "subjective"

elements, without compromising the objectivity of cognition.

[38] It is possible for a subject's ability to think about the

frame (or frames) of reference to rest on a subject's ability to

think about particulars within the frame(s) -- as well as

conversely -- only because the subject's grasp of which

particular object is in question is not exhausted by his grasp of

the object relative to the frame(s) of reference. This

independent understanding of the particular object is not

possible for thought about chess pieces, but is possible for

thought about the house downtown. What provides for this

difference of understanding? What allows for knowledge of a

particular not to be exhausted by frame-relative knowledge? In

discussing the example I suggested that frame-relative

understanding, if it is not to be frame-dependent, must rest on a

level of cognition which coordinates amongst different frames of

reference. And I want to suggest that these coordinations are

possible only because both object and subject are situated in an

active information environment which allows the

subject to orient with respect to the object. (Contrast this

with the relation between subject and object in -- and out of --

the Strawsonian shape-world). I cognize the house conceptually

by means of the frame of reference provided by the street grid:

number 12, 32nd street, etc. but my cognitive resources

for epistemic access to the house are not exhausted by this and

other frames of reference because I also have available to me

trails of information that lead through the information

environment to the house, and can flexibly guide activity which

is oriented towards the house. These trails of information

provide me with ways of cognizing the house which are not

relative to the street grid or other frames. I am suggesting, in

effect, that for singular thought to succeed -- for the

identification of the object not to be frame-dependent -- it must

rest upon ways of understanding in which the world is given to

subjects as trails of information through an environment of

activity.12

[39] The active information environment -- if it is to sustain

successful singular reference to the object -- must situate both

the subject (in that it is a space in which the subject can act)

and it must situate the object (in that it is a space with

respect to which the object has its identity). This can break

down in various ways; I will consider a couple of examples in a

moment. But we should recognize immediately that the notion of

an active information environment is as subjective as it is

objective; it is certainly not a notion of an absolute spatial

framework. In order to get a better idea of both subject and

object being jointly situated in an active information

environment it will help to contrast Evans's notion of an

information link, with the information trails,

which I discuss (briefly) here.13

[40] An information link exists only when a subject is

experiencing an object, typically in perception. An information

link can allow a subject, without inference, to form

observational judgements about the object.14 A subject may judge

that that object on the table in front of the subject is

spherical on the basis of a visual information link, where the

information link sustains the observation judgement without

requiring any inferential structure. S does not have to

form two judgements: that the j object

is spherical, and that that is the j object, on the basis of which S can

infer that that object is spherical. Rather, the information

link puts S in a position to straightaway judge that that

object is spherical. Moreover, an information link maintains

epistemic contact between subject and object over time, so that

the subject has an unmediated disposition to change his

observational judgements over time as the properties of the

object change. Evans's information links are individualistic:

different information links for different subjects. They are

largely subject-centred: the work of maintaining the link goes

on mostly within the information-processing systems of each

subject. And they are sub-personal: although the

deliverances of a link are personal, the link itself is

not part of a subject's cognition, either in experience or in

thought. For this reason we cannot talk of the content of the

link itself, only of its deliverances.

[41] For Evans, the content of the deliverances of an

information link has two components: it is standardly conceptual

for the predicative component, which "can be specified

neutrally, by an open sentence in one or more variables"

(124). The non-predicative component is egocentric: it

presents the object as standing in a bodily relation to the

subject, which may be specified within the theory of content by

means of a set of bodily axes, with the subject's body at the

origin of the space.

[42] Peacocke (1983) motivated his claim that Evans's

requirements for non-fundamental singular thought were too

stringent by considering a subject in a fairground who sees an

apple through a complex array of mirrors, some of which may be

moving in ways unknown to the subject. In this case the subject

enjoys an information link with the apple which puts the subject

in a position to form, without engaging in any inference, correct

observational judgements about, for example, the color and the

shape of the apple. Moreover, the apple appears in the subject's

perceptual experience as having an apparent position in

egocentric space, though in fact the apple is not at this

apparent position in egocentric space. The subject does not know

where in egocentric space the apple is, or how far it is from

him; a lack of knowledge which is manifested in his inability to

reliably point in the direction of the apple, or to be able to

walk reliably towards the apple. On Evans's account there can be

no adequate singular demonstrative thought about the apple in

this case because the subject neither knows where the object is

in objective space, nor does he know where it is in egocentric

space. That the subject nevertheless enjoys an information link

with the apple secures at best only descriptive thoughts

about the apple, such as the thought *the apple which is

causally producing these images is juicy* where the subject

refers singularly to a component of the information link

("these images") but only descriptively to the apple.

Peacocke's line by contrast is that the information link is

sufficient for a singular demonstrative concept so long as

"some conceivable additional evidence, experiences, and

devices ... would allow the subject to locate the presented

object". Now, this can't be right as it stands. As

McDowell comments, "the bare existence of any

information-link at all will make it conceivable that additional

evidence, and so forth, would enable the subject to locate the

presented object; Peacocke's supposed extra requirement adds

nothing..." (McDowell 1990: 259).

[43] But nor is it correct to return to the strict position

which requires actual knowledge of position in egocentric space.

Given Evans's notion of an information link it looks as if

Evans's strict position and Peacocke's liberal position are the

only options: either the information link produces an egocentric

deliverance which locates the object for the subject, or else it

does not. In the latter case, since the link itself is

sub-personal for Evans, it would only be by "investigating

the details of the perceptual link" that the information

link could sustain knowledge of which object was in question.

But that would be descriptive, not singular, knowledge: "If

the subject's thought can make contact with the apple in

Peacocke's fairground case, as it perhaps can if the subject

knows in general outline about the peculiar nature of the

perceptual link between him and the apple, the 'know which'

requirement is satisfied only in a completely different way: here

it is the idea of the information-link between subject

and object, rather than the information-link itself... that

carries the subject's thought to the right object" (McDowell

190: 257-58). But McDowell15

here misses the possibility that the information link

can be available cognitively to the subject as nonconceptual

content, and therefore not via the idea (a concept) of the

link. The idea is that the information link itself (not just its

deliverances, but the whole trail) is experientially available to

a subject as part of the environment of activity, as salient

forms of guidance within the environment of activity.

Because the trail itself is experientially available, the subject

has unmediated, but still rational dispositions to go this way

rather than that, or to judge that there is the house. Such

actions and judgements are not the products of two-stage

cognitive procedures mediated by a concept j: First I judge that I should go the j way, and then I judge that that is the

j way; so I go that way. Rather I am

in a position to see straightoff which way to go, because

I see the forms of guidance, a part of the trails, laid out

before me. I do not need to see the whole trail, only enough to

start me on and then, at each moment, to keep me on the trail;

the information environment does the rest.

[44] If, as theorists, we use this notion of information trails

through the environment, rather than the notion of an information

link, we can secure genuine epistemic constraints on singular

thought without the excessive requirement of actual knowledge of

egocentric location. What matters about the fairground mirror

example is whether or not the subject's information environment

-- as it can be made available, perhaps only in parts, in the

experience of the subject -- is structured sufficiently for the

subject to orient in the space of the object. Do the forms of

activity guidance allow the subject, knowingly and reliably, to

move towards the object, correcting for missteps if they occur?

Do the forms of activity guidance allow the subject, knowingly

and reliably, to retrace her steps so as to bring the object into

view again? Do they allow for the knowing and reliable

reproduction of object-directed activity? Given features like

the fairground's rotating mirrors it is unlikely that the answers

to these questions are positive in this example; but the point is

that the theorist of content needs to ask these kinds of

questions: it is not just the private, egocentric deliverances to

occurrent experience that matters but rather how an

intersubjective information environment is structured by

information trails, parts of which may be available at a time in

subjects' experience. If such an information environment is well

structured and allows a subject to orient their activity in an

object-directed way, then the information environment provides a

nonconceptual foundation for singular thought.

[45] Similar points can be made about less gerrymandered

examples. It seems correct and important that I can think a

singular demonstrative thought about Hunter Rawlings16 even though

I have never met the man, would not recognise him if he were in

the room today, do not know if he is and where he

is in my egocentric space, nor do I know where he is in space

given objectively. And I say this even though I agree with Evans

about Russell's Principle and about the falsity of the causal

theory of singular thought, according to which it is sufficient

for singular thought that my mental representations be at the end

of an appropriate causal chain whose initial links were caused by

the object which is the referent (Evans 1982, chapter 4). The reason why I can think

singular demonstrative thoughts about Hunter Rawlings even though

I fail to satisfy Evans's requirements for singular thought about

him is that I am plugged into a rich information environment

structured by a multitude of information trails that can guide

action in a Hunter Rawlings appropriate way. The example is

similar to the earlier example of my singular thought about the

house downtown. In this case I can satisfy Russell's Principle

with respect to Hunter Rawlings, even though I don't know his

location, because his identity is currently socially embedded

within the University and I am plugged into a rich set of

socially mediated information trails that guide my action in a

way which is appropriate to an object with that kind of socially

determined identity. The subject, in this example, is located in

an active information environment in that the subject is able to

find their way through the environment; the object is located in

the same information environment, and its location in the

environment is, in part, constitutive of the identity of the

object. (It is not, of course, necessary that the subject

actually does locate the object).

[46] We are now in a position to return to the argument against

a detachable fundamental level of "wholly" objective

thought. There is a second argument against the

"objectivist" conception of the fundamental level, which

rests not on the characteristic asymmetry of frame-dependence,

but on the necessity in frame-dependent reference for the frame

itself to be co-presented along with the object of thought. We

can introduce this argument via a discussion of an inadequate

active information environment; not, this time, Peacocke's

fairground case, but Evans's television example.

[47] When Evans argues that information links are not sufficient

for singular concepts he does so in terms of an example of a

soccer player seen on a TV screen, and he argues that because of

the circuitousness of the information channel the subject is not

in a position to think non-descriptive thoughts about the soccer

player. I think that it is fair to say that many readers have

not been convinced by Evans's example, and that perhaps even more

have failed to understand it properly. A proper discussion of

that example would involve a discussion of the generality

constraint, and I want to avoid that here. So what I will do is

to alter Evans's example in a way that avoids some of the

difficulties. One source of difficulty is that people often

imagine that the viewing subject may recognize the soccer player,

and that this recognitional ability would ground their singular

thoughts about the player. And, secondly, even if the viewing

subject does not recognize the player, surely the subject is

plugged into an information environment in which there are

information sources who would recognize the player, and

through which the television transmission can be tracked allowing

the subject to discover the identity of the player by for example

finding in the newspaper which match was being shown on that

channel at that time. We can avoid these difficulties by

supposing that the TV images are images of coke cans, not soccer

players, and that there are no information trails, for whatever

reason, which lead from the TV display back to the source of the

transmission. You can imagine, if you like, bizarre Peacockian

fairground-style shenanigans which render the information links

untrackable.

[48] Suppose that an image of coke cans appears on a

television screen, (and we do not know, nor have we any way to

track where the information is coming from). One of us then

points (as we might say, "to a coke can") and says something (as

we might say, "about the coke can"). If I have identified some

particular object then I have done so only relative to the frame

of reference established by the television screen: my

identification is frame-relative. My capacity to think about a

particular coke can, which is sustained by the information

provided through the TV, must exploit the frame of the TV:

for example, the can which is presented at the top left of the

screen. It's not that I must entertain such a descriptive

thought which locates the can relative to the screen, but just

that what I do entertain can only have a semantics, an

interpretation which fixes a particular coke can, relative to the

informational frame of the TV. The semantic interpretation

includes the informational frame whether or not I am conscious

of, or explicitly think of, the frame. For without such a frame

to anchor my reference, I may attempt a singular demonstrative

thought about the can -- *That can is made of aluminium*

-- , but the semantic link to the can is sustained only

descriptively: *The one and only can that I am now seeing

through this information channel which is at the top left hand

corner is made of aluminium*. Likewise for thoughts like

*The shiniest can is made of aluminium*, and *All the cans are

made of aluminium*. As in the discussion of *The tallest Cornell

Professor*, the content of these thoughts is fixed relative to a

given totality, of cans or of Professors. But in the case of the

cans, the totality is fixed not by an independent identification

of individuals within the totality but by the frame of the

information channel.

[49] Notice how this case is different from my thought about the

house downtown. In that case I have frame-independent knowledge

of which house it is because I can exploit a complex environment

of information trails that lead downtown and enable me to locate

the street grid frame of reference relative to other sources of

information. And someone might say that in the coke can case I

can similarly exploit my knowledge of the location of the frame

of reference; that is, of the location of the TV. But this won't

work, and seeing why it won't work shows up some similarities to

the Piggy case. There are available to me information trails

which lead downtown, and in virtue of which I know where downtown

is. But these information trails are not part of the

semantics of my thoughts about the house: they do not

enter into the determination of the truth value of these

thoughts. Without the information trails there would be nothing

which would constitute my semantic understanding of sentences

about the house, but there is no sense in which my thoughts are

about the trails. The trails make for the possibility of

my singular thought, but they do so at a nonconceptual level of

cognition: the trails themselves are not co-presented with the

object in the subject's thought, but only -- and occasionally --

in experience. Not so for the coke can thoughts: for them, the

information channel is part of the semantics. It is because of

this -- as well as, and related to, the characteristic asymmetry

-- that the TV-link can sustain only frame-dependent

thoughts.

[50] The house, identified relative to the grid of streets, is

in the same space as downtown. Hence our knowledge of the

location of downtown can ground our knowledge of the location of

the house. But the coke can is not in the same space as the TV:

the epistemic resources which are sufficient for the subject to

act and judge appropriately in the environment of the TV are not

sufficient for the subject to act and judge appropriately in the

environment of the coke cans. (There is no single active

information environment which situates both subject and object,

and is such that the object's location in it is, in part,

constitutive of the identity of the object). Therefore our

knowledge of the location of the TV cannot ground our knowledge

of the location of the can of cola: the location of the TV

provides only a virtual space for the cola cans. Indeed,

the information channel available to us does not tell us anything

about the spatial relation (either direction or distance) of the

coke can to the observer, or to any object whose location is

already known to the observer. It only provides information

about the location of the coke can relative to other coke cans in

the virtual space defined by the frame of the TV. The

information trails which provide epistemic access to the frame of

reference do not provide any epistemic access to the coke cans,

whereas the trails which provide access to downtown do

provide epistemic access to the house. In both the coke can

utterances and the Piggy-references the object is identified

relative to a frame which bears the wrong kind of epistemic

relation to the subject and the object. Piggy's frame of

reference can itself only be identified in literary space, as an

abstract production of William Golding's, etc. Knowledge of that

space is of help only in identifying entities, such as a literary

work of art, with an abstract ontology, rather than the material

ontology of Piggy-the-schoolboy. That's why knowledge of the

book "Lord of the Flies" fails to provide us with any

conception of what it would be to identify Piggy in the street.

Knowledge of the literary space may help in identifying

Piggy-the-literary-archetype, but then knowledge of the frame of

reference provided by the TV helps in identifying the coke

can-qua-visual-image. Only if we change the ontology can

reference to the frame, or knowledge of the location of the

frame, provide a way to avoid the frame-dependence of reference

to Piggy or to the cola can: from Piggy-the-boy to

Piggy-the-abstract-archetype, or from the solid-material-coke-can

to the coke-can-as-set-of-pixels. In such cases thoughts about

the objects (Piggy, the coke can) require the semantic presence

of the frame of reference; the frame itself enters into the